“If a teacher tells me what to do, I’m not really thinking” – Third Grade Student

Lately, many educators have been discussing the importance of learner agency and, as many people know, the new enhancements to the International Baccalaureate’s Primary Years Programme (PYP) will be introduced in 2018. The enhancements will offer a deeper focus on agency. I’ve read a lot of exciting blog posts and tweets regarding the upcoming changes. Many educators are naturally asking themselves WHAT these enhancements will mean for their schools and HOW they will implement them. As an educator who runs a choice-based Visual Arts programme in an IB World School, I’m keenly interested in agency. Over the past two years, I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on and researching the WHY in my classroom and it has transformed my practice. As I anticipate the enhancements to the PYP, I have been curious to go deeper with the WHY for agency and I encourage other educators to reflect on and research the WHY for agency in their own practice.

(IB, 2017)

What is agency? According to the International Baccalaureate,

Agency is the power to take meaningful and intentional action, and acknowledges the rights and responsibilities of the individual, supporting voice, choice and ownership for everyone in the learning community.

Agency is present when students partner with teachers and members of the learning community to take charge of what, where, why, with whom and when they learn. This provides opportunities to demonstrate and reflect on knowledge, approaches to learning and attributes of the learner profile (IB, 2017).

Why should we focus on Agency?

For an answer to that question, a good place to start is The End of Average – How to Succeed in a World that Values Sameness by Todd Rose (2016).

The Science of the Individual

Rose (2016), in his fascinating book, describes himself as a high school dropout with a D-minus average. By the time he was 21, he was married with children and trying to support his family with a stream of low-wage jobs. One might have thought that he was on a road to a life filled with poverty and struggle. If we fast forward to today, Todd Rose is the director of the Mind, Brain and Education program at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. What he has learned about the Science of the Individual and himself along the way is the secret to his remarkable transformation and the subject of his book.

Designing for No One

In his book, Rose tells how, in 1952, the US Air Force was trying to figure out why they were having so many problems with their fighter jets. At first they blamed the pilots. Then they blamed the technology. Next they blamed the flight instructors. But it turns out that the problem was the cockpit. The cockpit had been designed to fit the average pilot’s body. Lieutenant Gilbert S. Daniels was asked to conduct a new study of the dimensions of the pilots, since the last time the Air Force had conducted such a study was almost three decades prior. Daniels measured over 4,000 pilots on ten physical dimensions. Air Force researchers thought that most of the pilots would fall within the average range on all dimensions. But what Daniels found was that no pilots were within the average range on all dimensions. Not a single pilot. By designing a cockpit for the average pilot, the Air Force had “designed a cockpit for no one”. The Air Force took these findings seriously and made a bold move. They demanded that the cockpits be “designed to the edges” of the dimensions of their pilots. The final results were things like adjustable seats (we use these daily now!) and adjustable instruments (Rose, 4).

The Average Man and the Averagarian Approach

Rose is a researcher and a specialist in the Science of the Individual. He details the fascinating timelines, historically significant events, scientists, and research findings which led to the first practices of collecting large amounts of data from many individuals and averaging them to look for ways to make sense of society, education, medicine, and industry.

Adolphe Quetelet was one of those early scientists. Born in 1796 in Belgium, Quetelet borrowed the method of averages from astronomy to form his social science and was responsible for promoting the concept of the average man, according to Rose (26-31).

The Impact of the Averagarian Approach on Industry and Education

Rose writes that Frederick Winslow Taylor was responsible for the standardization of the work environment. In the 1890s, Taylor was working at a steelworks company when he began to look for ways to improve the speed of various tasks, standardize them to the “one best way”, and time them for efficiency. Even today, anyone who has worked in a factory or production environment has probably worked within the approaches for standardization that were first introduced by Taylor (Rose, 40-45).

By the early twentieth century, this “Taylorist” approach of standardization within the industrial world had a profound influence on education in the United States. “The educational Taylorists declared that the new mission of education should be to prepare mass numbers of students to work in the newly Taylorized economy.” (Rose, 50) By 1920, students were provided with one standardized education.

Edward Thornkike advocated for sorting students according to their ability. The fast learners (believed to be the talented students) were identified and had a clear path to college. The average learners were expected to take up jobs within the Taylorized economy. The slow learners were given little support (Rose, 52-56).

These influences on industry and education are still present in society today in the form of employee rankings, standardized tasks, efficiency ratings, standardized tests in schools, grading systems, standardized text books, bells to signal the end of each class, IQ ratings, personality tests, etc.

The Research and the Three Principles of Individuality

What does the research tell us about things like averages, IQ tests, grades, etc. in relation to the individual? Like the story of the Air Force fighter pilots, over and over again, Rose details how averages can range from uninformative to terribly misleading when it comes to describing or trying to understand any one individual.

If the research is telling us that averages are not adequate in trying to understand the individual, what other approach might work? Rose outlines three principles of individuality: the jaggedness principle, the context principle, and the pathways principle.

|

The Jaggedness Principle

|

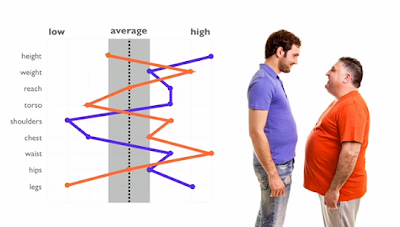

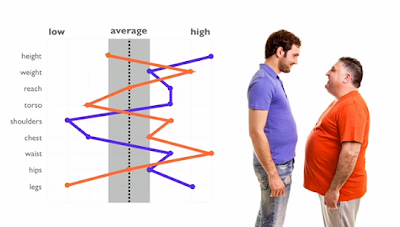

Rose (81) explains that we often simplify things in our mind to just one dimension. For example, if we think about size, we might think about a person being large, medium or small. However, the reality is that people come in all shapes and sizes, so that their dimensions create a jagged profile. See example below.

(Rose, 2016)

A one-dimensional approach of large, medium or small fails to capture the true nature of human size (Rose, 82). Additionally, looking at the average fails to capture the true nature of size.

The same is true for talent and intelligence, according to Rose. Yet, businesses and schools continue to look at one-dimensional factors mentioned above such as employee ratings, standardized test scores, grades, IQ scores, grade-level textbooks, etc.

The Jaggedness Principle in the Visual Arts Class

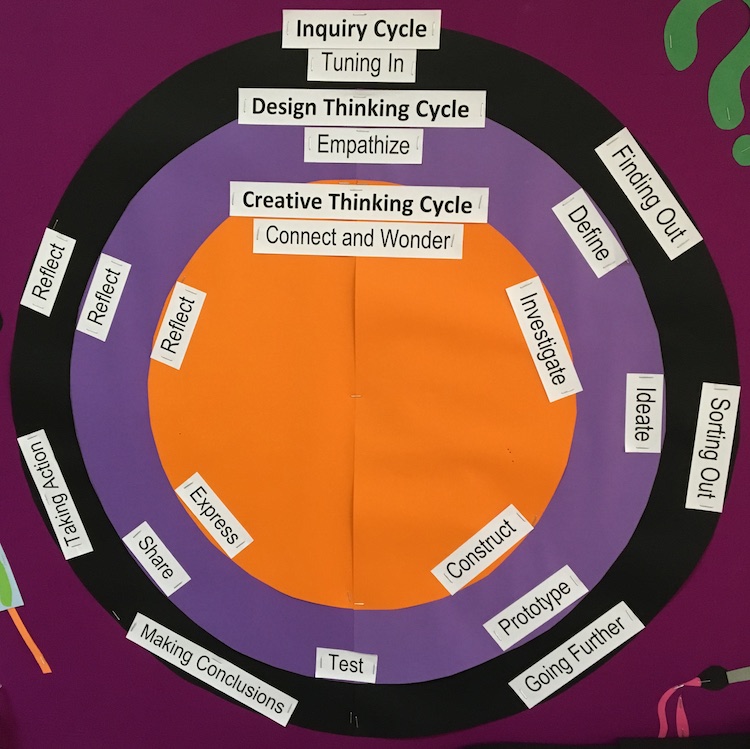

When students partner with members of the community and take charge of “what, where, why, with whom, and when they are learning” (IBO, 2017), they are developing across multiple dimensions. The jaggedness principle tells us that each individual is unique across these multiple dimensions. When students approach learning from their own particular dimensions, perspectives and interests, they will grow and develop at the pace that is best for them and in a way that sparks genuine curiosity, as they follow their passions.

For the past 100 years, Visual Arts classes around the world have not changed much (Hathaway, 2013). The practice of introducing adult art to children and having them copy either the paintings or the style has become something that we expect from art programmes (Hathaway, 2013). The results of such lessons are often quite pleasing to the adult eye and we deceive ourselves into thinking that the students have been creative and interested in the learning. I used to approach my classes in the same way. After some honest reflection, I realized that cookie-cutter lessons are neither creative nor interesting for the students. Like the findings from Rose in his book, students come to the Visual Arts class with a variety of interests, passions, knowledge, skills and developmental levels. Their profiles are jagged. Giving the students agency (giving them a choice, voice and ownership of their learning) makes sense because one size does not fit all.

|

The Context Principle

|

“…(T)he context principle…asserts that individual behavior cannot be explained or predicted apart from a particular situation, and the influence of a situation cannot be specified without reference to the individual experiencing it.” (Rose, 106). What this means is that personality traits we often use to describe someone are not consistent in all contexts. Rose gives the example of “Jack”.

IF Jack is in the office, THEN he is very extroverted.

If Jack is in a large group of strangers, THEN he is mildly extroverted.

IF Jack is stressed, THEN he is very introverted. (106)

Yet we tend to think of people as either extroverted or introverted; honest or dishonest; aggressive or non-aggressive; or creative or not creative. The context principle illustrates that our traits are influenced by the context in which we find ourselves. Additionally, not all people respond to specific situations in the same way.

The Context Principle in the Visual Arts Class

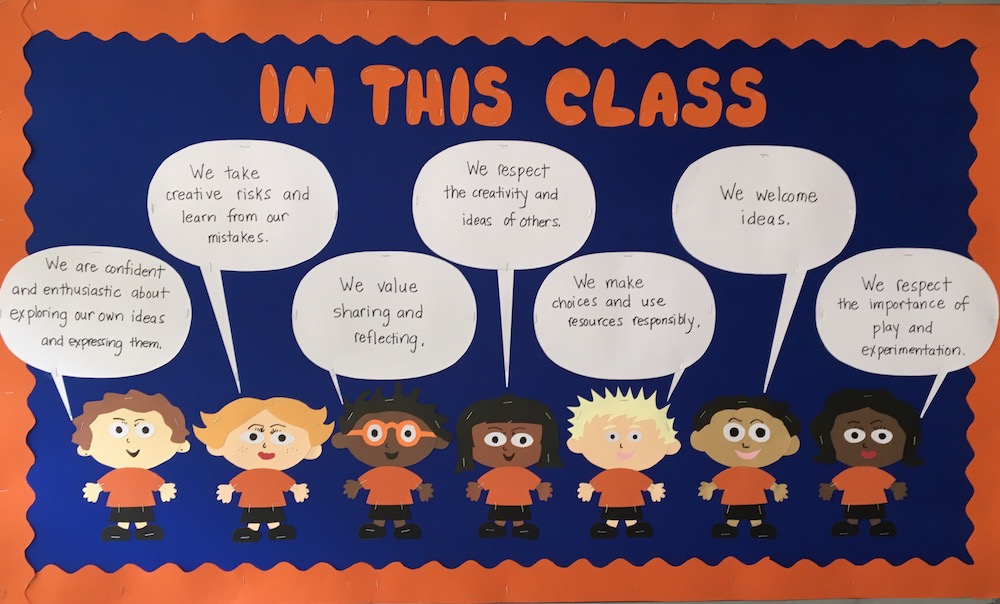

Through the context principle, we learn that each student reacts to various situations differently. Therefore, as teachers and members of the community are partnering with students, we must understand that part of our responsibility is to create a range of opportunities so that each student will be successful. That means offering students agency to choose options that provide the best context in which the students will thrive.

In my Visual Arts class, I used to decide on the lesson idea, choose the materials and try to scaffold everything in such as way so that there would be little or no failure within the class. However, no matter how much I tried to infuse my own excitement into the class and scaffold the lesson, there were inevitably cries of “I can’t do it!” “Do we have to do this?” “Is this good enough?” Now my approach is radically different. I now use an approach that is similar to the Reading and Writing Workshop Model for children’s literacy (Children’s Literacy Initiative). The concept is simple: IF Jack is reading something that he loves THEN he is likely to read longer and think more deeply about his reading. This will have an obvious effect on his literacy development. Similarly for Art, the approach I use is called Teaching for Artistic Behavior which regards students as artists, supports different needs and interests of students, and creates choices for multiple learning opportunities. (TAB)

Now, my classroom is designed with context in mind. Students are presented with a classroom full of interesting materials to explore (cardboard, sticks, a variety of paints, coloured papers, clay, fabric, wool yarn, glue, scissors, etc.) The art room is a safe space where students are invited to explore materials and express their ideas. Mini lessons offer artists and concepts to think about, skills and tools to practice or reflection time. The rest of the time is spent supporting students to discover contexts in which they thrive. IF Jack is exploring his own passions and curiosity THEN he is likely to be more engaged and take more ownership of his learning.

What I’ve discovered is that curiosity usually leads to something more challenging. For example, many elementary students love to make paper airplanes. One first grader recently commented to me that learning how to make a paper airplane was one of the highlights of her year. Given the freedom of choice and materials to explore making paper airplanes students might make planes until they are tired of folding papers. What happens next is important. Once they see all of the paper airplanes on the table, someone might have the brilliant idea that they should build an airport. Now a group of students is exploring architectural modeling, all the while developing spatial reasoning and collaboration skills. One second grader recently commented about an airport he built with his classmates, “I didn’t think I could build something that big. It helped my confidence grow.”

Later the same students might decide to build a model of a city or paint a map and develop a story that goes along with it. Yong Zhao said, “When a child has a reason to learn, the basics will be sought after, rather than imposed.” (Zhao, 2012) The context principle explains why the proper context helps students develop their own reasons to learn. This leads us to the next principle: the pathways principle.

|

The Pathways Principle

|

Edward Thorndike introduced the idea that “faster equals smarter” into the educational system (Rose, 130). But, are speed and learning ability really related? In the 1980s, Benjamin Bloom conducted a research study in which two groups of students were taught a subject that they did not already know. The first group (“fixed-pace group’) was taught during fixed periods of instruction that were standard at the time. The second group (‘self-paced group’) was taught the same material over the same total amount of time, but they had a tutor who permitted each individual to go at their own pace (sometimes quickly and sometimes slowly). In the first group, 20 percent of the students achieved “mastery of the material” (a score of 85 percent or higher). In the second group, 90 percent of the students achieved a mastery score. With flexibility in the self-paced group, most of the students performed very well (Rose, 132).

If not all students learn at the same pace, what about sequence? Do all students learn in the same sequence? Kurt Fischer is a scientist in the field of the science of the individual. According to Rose, Fischer has studied a wide range of developmental issues, such as how young children learn to read (137). For example, Fischer discovered that there are three distinct sequences in which a child might progress to learn to read single words. Fischer recognized that two of the sequences have similar results, however, the third sequence results in reading difficulties. As a result, now children who follow the third sequence can be identified and receive the proper support.

From his research, Fischer suggests that we use the metaphor of a “web” to describe the process in which each step we take in our development opens up a range of possibilities (Rose 138).

The Pathways Principle in the Visual Arts Class

The pathways principle teaches us that each student’s learning journey will be a unique path in which the next steps are revealed as the student makes progress in their learning. Giving students opportunities for agency will give them the power to make meaningful and intentional action as a result of their learning and such action will illuminate the path to next steps in the student’s journey as they reflect on their knowledge and approaches to learning.

In the Visual Arts class this year, there is a grade four student who started the year without much confidence in his own art-making skills. After some exploration and discussion, he started making geometric designs with a ruler on paper and then carefully colored them. Next he started a collage project cutting out geometric shapes. He immediately asked permission to abandon the collage project because he had something bigger in mind. Now he’s working on a large poster-size painting of a cityscape (using the skills he learned with the geometric designs). He asked me if I could display his painting in the room and ask students from other classes to offer him some feedback. Recently, he saw me working on two large canvases 2.5 meters tall with the grade five class. He asked if his next project could be on such a large canvas. I suspect that we have an installation artist in the making, as his projects grow larger and more complex with each step.

A third grade student has taken a very different path this year. She started the year making large expressive abstract paintings with bold, bright colors. Lately she has been exploring model making as she collaborates with a classmate to build miniature furniture models. Last week they designed and built a model car together. Two other students in the same third grade class have spent most of the year on a series of elaborately detailed drawings for shoe designs, taking breaks in between designs to do small 3-D modeling projects. “If a teacher tells me what to do, I’m not really thinking,” commented one of the shoe designers.

All of these students can describe their learning journey in the Visual Arts class this year. Because they were given opportunities to express their agency, they each thrived as they explored different pathways.

It’s Time for Agency

The jaggedness principle, the context principle and the pathways principle provide us with answers to WHY agency is important. Like the one-size-does-not-fit-all lesson the US Air Force learned in 1952, it’s time for educators to respect student agency and partner with the learning community to fit each student’s educational experience to their own individual, multidimensional traits and characteristics. It’s time for educators to present students with opportunities to choose contexts in which they learn best. It’s time for students to be given permission to follow pathways that make sense for each individual. Knowing what we know now, it’s time for a greater focus on agency. As a Visual Arts educator, I want to be committed to helping students, as individuals, develop their learner agency, make choices that are relevant to them, express their own voice, and take ownership of their interests and learning.

Resources:

Children’s Literacy Initiative. Reading and Writing Workshop. https://cli.org/resource/reading-writing-workshop/

Hathaway, Nan E. (2013). Smoke and Mirrors: Art Teacher as Magician. Art Education. http://teachingforartisticbehavior.org/wp-content/uploads/ArtEd_May13_Hathaway.pdf.

IBO (International Baccalaureate). November 2017. The Learner in the Enhanced PYP. https://resources.ibo.org/pyp/topic/PYP-review-updates/resource/11162-46068/data/p_0_pypxx_amo_1711_1_e.pdf. Accessed 26 May 2018.

Rose, Todd (2016). The End of Average – How to Succeed in a World that Values Sameness, Allen Lane, USA/UK.

TAB (Teaching for Artistic Behavior). http://teachingforartisticbehavior.org/resources/sample-page/about-us/

Zhao, Yong (2012) “World Class Learners: Educating Creative and Entrepreneurial Students.” Corwin.